Revenue Recognition: What Is the Actual Sales Price?

The Potentially Misleading Impact of Adjustments for Variable Consideration

In our last two installments, we explored the concept that adjustments must be made to sales to account for the fact that not all revenue that is billed will ultimately be collected and how extending payment terms can help a company boost revenue in the current quarter at the expense of future quarters. In this installment, we will explore how the effective sales price used to calculate a company’s revenue is influenced by what accountants refer to as variable consideration arrangements.

To most people, calculating sales seems like a simple proposition. One just takes the number of units purchased multiplied by the number on the price tag. However, in practice, the net amount of what a company ends up receiving for its products can be influenced by items such as volume discounts, coupons, rebates, and sales returns. The impact of all these items often depends on the outcome of events in the future that are not known at the time of the sale. This requires the company to estimate what the impact of these developments will be when calculating its net sales in the current period. In addition, companies may pay fixed amounts such as slotting fees and the cost of placing in-store displays which also act as a reduction of gross sales.

For example, here is some of the revenue recognition disclosure for Conagra Brands (CAG). Descriptions like this are found in the notes to financial statements in the 10-K reports.

“Revenue Recognition — Our revenues primarily consist of the sale of food products that are sold to retailers and foodservice customers through direct sales forces, broker, and distributor arrangements. These revenue contracts generally have single performance obligations. Revenue, which includes shipping and handling charges billed to the customer, is reported net of variable consideration and consideration payable to our customers, including applicable discounts, returns, allowances, trade promotion, consumer coupon redemption, unsaleable product, and other costs. Amounts billed and due from our customers are classified as receivables and require payment on a short-term basis and, therefore, we do not have any significant financing components.

We offer various forms of trade promotions and the methodologies for determining these provisions are dependent on local customer pricing and promotional practices, which range from contractually fixed percentage price reductions to provisions based on actual occurrence or performance. Our promotional activities are conducted either through the retail trade or directly with consumers and include activities such as in-store displays and events, feature price discounts, consumer coupons, and loyalty programs. The costs of these activities are recognized at the time the related revenue is recorded, which normally precedes the actual cash expenditure. The recognition of these costs therefore requires management judgment regarding the volume of promotional offers that will be redeemed by either the retail trade or consumer. These estimates are made using various techniques including historical data on performance of similar promotional programs. Differences between estimated expense and actual redemptions are recognized as a change in management estimate in a subsequent period.”

So, the sales figure on the income statement does not simply equal “price x volume.” Companies estimate the potential for returned merchandise, volume discounts earned by customers, coupon usage, etc. Often, these amounts are not material or do not change much from period to period. Moreover, many companies do not disclose all this information quarterly and may not quantify it at all. Analysts often need to look for clues in this area when sales figures look much higher or lower than expected. We will examine some of the more common adjustments to sales below.

Volume Discounts and Rebates:

Many companies incorporate volume discounts into their contracts with customers. This is a common practice among pharmaceutical companies. It is important to remember that these discounts do not apply to a single transaction like the typical “buy one, get one half off” deals available to you at the store or online. These contracts can run over a year and establish a pricing schedule based on how many units a customer buys over that timeframe. For example, a hardware chain may sign a contract with Shovel Company under which it will pay Shovel $25 for the first 500,000 shovels it buys that year, $22 for the next 150,000, and $20 thereafter. Many assume that Shovel will simply use $25 as the sales price for the first shovel it sells to the hardware chain that year. However, accounting rules require that Shovel must estimate the sales price of each unit as an average price received for all shovels sold under the contract that year. This requires Shovel to estimate how many units it will sell to the hardware chain that year and incorporate this as a reduction in reported sales. In addition to volume discounts, companies may offer discounts for faster payment. In instances like these, a company must make an estimate of how much and when these events may occur and that estimate becomes a net reduction to gross sales. Also, it may adjust these forecasts and start to accrue more or less based on how actual results are progressing over the year. These adjustments can have a material impact on reported results.

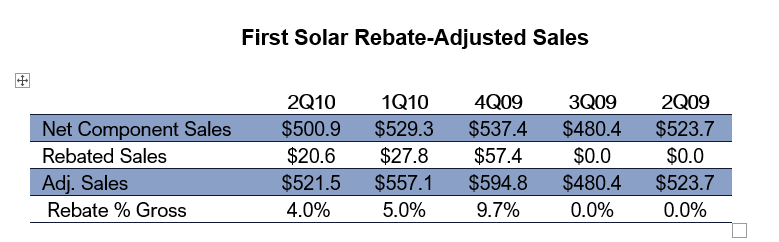

An example of the impact of rebates can be seen in the results of First Solar which we discussed in our last column. The solar panel industry was getting competitive and pushing down selling prices for solar panels faster than anticipated. First Solar had long-term contracts with several customers who were not going to pay the previous prices when comparable panels were selling for less. This led First Solar to rework its contracts with several of its larger customers. First Solar’s prices would more closely match the declining market prices with a rebate mechanism built in. If panel prices were expected to decline by 5%, customers would get a 5% lower price from First Solar. PLUS, if the panel prices in the market actually fell by 8%, First Solar would rebate another 3% back to the customers giving them the full 8% decline. These rebates quickly became a significant drag on reported sales and sales growth turned negative.

Other examples of rebates are seen with some retail stores that offer to match the lowest price found in the market. If they are selling a new TV for $1,000 and customers find another store selling it for $925, the store where they bought it will rebate $75 to the customer. It has been a while, but some of the computer and car companies used to give rebates as a way to get a short-term loan from the customer. These deals might say, “buy a new computer for $1,800 before the end of the month, and we will give you a $200 rebate in 35 days.” The customer might have financed the $1,800 via a credit deal offered by the company for 36 months, but before the first payment is due, the customer gets $200 in cash. In all these examples, the seller must estimate how much of the rebates are likely to be paid, accruing for them as a contra-account and netting that against reported sales.

Promotional Spending

Often people equate promotional spending with advertising which is typically recorded on an operating expense line. However, promotional spending consists of non-advertising expenditures designed to help a company’s retail customers to promote the sale of its products to end-users. Such amounts can include the installations of in-store product displays and training the retail staff about the product. Coupons are another common form of promotional spending where a company must reimburse its retailer customers for coupons that are redeemed at the time of purchase.

Slotting fees paid to retailers are often a large component of promotional spending that is overlooked. Only so much space is available in a store and if a company wants to introduce a new product, it often must convince the store to replace an existing product by paying a slotting fee. It can also be charged for more prominent placement on the shelves like at the end of the aisle or at eye-level rather than the bottom shelf.

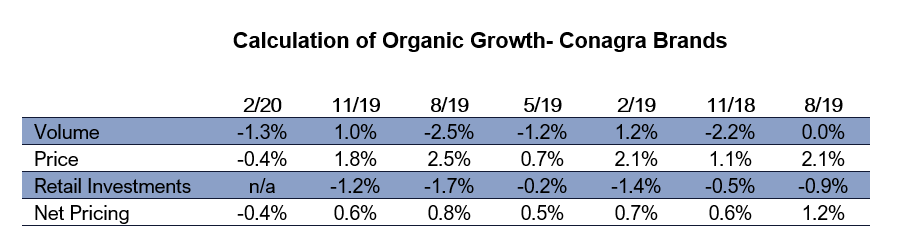

Promotional spending acts as a reduction in price. It has seen considerable attention with Covid because early in the pandemic, retailers’ shelves were empty, and they wanted any product available to fill them. Customers also bought anything available. Slotting fees, in-store displays, and coupons were not necessary to support sales. As a result, pricing appeared much stronger for many consumer products companies. Look at the case of Conagra Brands (CAG) before and during Covid:

The “Retail Investments” line reflects the impact of promotional spending. CAG stopped reporting this data in 2020 – (never a good sign but a topic for later). Notice how in periods when pricing gains were high, the promotional spending was also higher. In February 2019, 2.1% pricing was really only 0.7% net of retail investing.

As Covid hit, suddenly net pricing started to surge for CAG:

How did CAG suddenly see strong pricing? It cut promotional allowances!

In the August 2020 quarter, pricing rose 4.1%. However, CAG booked basically zero in promotional spending and actually reversed accrued expenses in this area which boosted reported revenue growth by 0.7%. Year-over-year promotional spending went from and drain of 1.7% on pricing to a positive 0.7%, a 2.4% swing.

In the November 2020 quarter, CAG guided investors to expect MORE promotional spending. Management said in the August 2020 conference call, “we expect to increase our marketing support both above the line [in-store spending that nets against sales] and below the line [in SG&A]. We believe there are opportunities to increase brand-building investments where capacity permits.”

Then in November, CAG actually spent less in this area. Management stated in the November 2021 conference call that “organic net sales was primarily driven by a 6.6% increase in volume related to the growth of at-home food consumption. The favorable impact of price mix, which was evenly driven by favorable sales mix and less trade merchandising also contributed to our growth.” CAG noted that half its 1.5% net pricing gain came from reduced promotional spending. Cuts to promotional spending added 75bp to net pricing.

For February 2021, CAG again noted that half its 3.6% pricing gain came from cutting promotional spending or 1.8%.

By August 2021, CAG saw promotional spending start to reverse as it boosted its trade allowances by $18.8 million which was a 70bp drag on pricing. Total pricing was up 3.1% with commodity inflation price hikes making up 2.3% of that. CAG was back to a more normal net pricing figure of only 0.8%.

Product Returns

We used to follow a now-defunct video game maker that was having difficulty duplicating the success of a hit game. It was normal for it to see seasonality in sales as the quarter ending in November was typically the largest. However, we noticed that it posted an especially strong November sales figure one year, which was breaking the negative trends it had been posting. We concluded that retailers were willing to stock anything in December and this company cleared out its warehouse (this was still when video games came on a cartridge and were packed in a box). Receivables rose as the customers didn’t pay the video game company in November. The company booked sales when the product was shipped. However, its customers had the ability to return unsold merchandise and we expected the February results to be significantly worse due to returns. We underestimated the size of the problem as returns of product “sold” in November actually exceeded new sales in February as customers returned unsold games rather than pay the invoice. As a result, the company reported a negative revenue figure for that quarter!

Larger companies with a broad product line seldom have significant returns. Places to watch for this type of risk are younger companies with one really popular product. Think of things that are sold on infomercials like an exercise machine or air fryers or a suddenly mega-hot toy that even Congressmen make jokes about while they still are stumbling around trying to dance the Macarena.

Markdowns are Common

Many people are familiar with markdowns from just shopping in various stores. Suddenly a package of razors that used to be $10 is on sale for $5. It’s now March and the $150 winter coat is now $80. What is normally happening is a new product is rolling out and shelf space needs to be cleared for it. You will often get clues that this may be coming if a company talks about a new product design or new packaging that is being rolled out. Rather than take back the unsold product and throw it away, a supplier will give the store an allowance to mark it down to sell it quickly. The store may not suffer in this situation, but the supplier would. If the store was paying $8 for an item and selling it for $10, it was making $2 in gross profit. A markdown may involve cutting the next invoice to the store by $5 which reduces the cost to the store from $8 to $3. It can then sell it for $5 and still make $2 in gross profit.

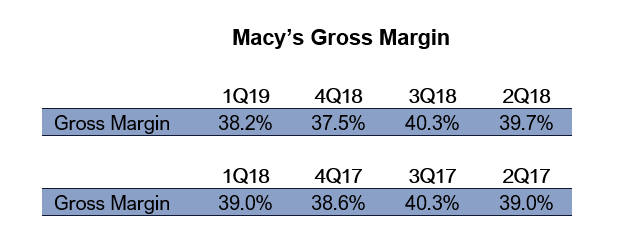

Often this shows up as some weakness in sales, but it often can make a bigger impact on gross margin. Here are some examples of this:

Macy’s noted that its 1Q18 saw fewer markdowns than normal. That made for a more difficult gross margin the following year. Going into 4Q18, Macy’s said it needed to reduce inventories more and therefore took more markdowns in that quarter which resulted in a year-over-year decline in gross margin which can be seen in the following table.

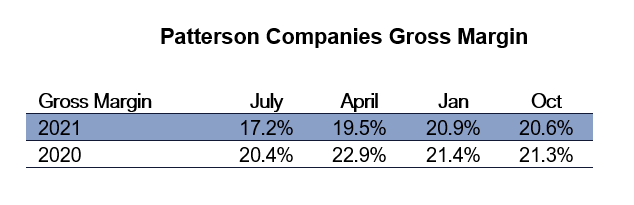

Another example is Patterson Companies (PDCO) which sells dental equipment and supplies. During Covid, it moved more heavily into selling masks, gloves, and sanitizer products. It saw this area as a long-term source of future demand. As many consumers already had a mask and mask mandates expired in many areas- the country was awash in Covid protection products. In the April 2021 quarter, Patterson announced it was writing down its Covid-related inventory by $11 million in response to declining prices. In the July 2021 quarter, Patterson marked its inventory down another $49 million and began donating these supplies to charity. The margins were helped by Covid-related product sales during 2020, but gross margins started to fall as that market lost its growth and pricing potential:

The $49 million charge in July 2021 cost Patterson 3.0% off its margin.

In the next installment of Peek Behind the Numbers, we will take a closer look at how companies account for their costs to obtain a contract and how changes in the related assumptions can materially impact reported results.

If you would like to subscribe to Peek Behind the Numbers for free:

Please share Peek Behind the Numbers with any of your interested colleagues and friends: