How Inventory Accounting Methods Impact a Company's Reported Earnings

-and Why It Is Especially Important in the Current Inflationary Environment

“Invest in inflation. It’s the only thing going up.” -Will Rogers

Inflation is all the news these days- which makes it the perfect time for investors to be considering the method of inventory accounting that each of their companies utilizes. In a perfect, inflation-free world, the various inventory accounting methods will result in essentially the same profit. Colgate-Palmolive noted in both 2019 and 2020 that its choice of accounting method for inventory costs would have had no impact on earnings. This makes us believe commodity inflation’s impact on accounting has not been explored in a long time.

However, in the current environment of skyrocketing raw materials, labor, and shipping costs, the various methods can result in drastically different reported profits depending on the method used and the number of times a company turns (sells) its inventory on hand. This week, we will examine the three main methods of inventory accounting and how they can potentially result in artificially higher profits in periods of raw materials inflation.

Description of Methods

Let’s assume a company has an inventory of units it has acquired over the last few months for $10 per unit. There is no inflation, meaning each unit it sells is replaced by a unit that cost the same as the unit just sold. As Colgate noted above, in such an environment its choice of inventory accounting method would not matter to results.

Let’s assume in Period 1 there is still no inflation and the company sells 5 units. Companies generally price their product based on what it will cost to replace the inventory at the current cost. This is why your gas station raises the price of gasoline as soon as oil prices rise even though the gas you’re buying was already in the station’s storage tank before the cost increase. The station needs to charge enough to pay for the next shipment of gasoline which will cost more. We will assume that the company in our example prices its products at the current cost plus $3. This will result in a selling price of the $10 cost plus the $3 add on, or $13. Thus, the sale of 5 units will generate first-quarter revenue of $65. The inventory was acquired for $10 so the cost of 5 units would be $50. The Period 1 (pre-inflation) results look like this:

However, the situation changes when inflation is introduced and the cost to replace inventory starts to rise. The company has to pay more for new items it is adding to its inventory. By the end of Period 2, the company’s inventory layers look like this:

Assuming the company sells five more units in Period 2, how should the company arrive at a cost for the 5 units it sells? Should it utilize the $10 cost basis of the units in Layer 1 or the cost of one of the other layers? This is one of the first concepts a student learns in a Financial Accounting class. There are three main methods utilized to calculate the cost of sales: the First-in First-Out (FIFO) method, the Last-in, Last Out (LIFO) method, and the Average Cost method.

First-in, First-out (FIFO)- As it sounds, the FIFO method expenses the inventory that was added first. In the above example, the company will expense the five oldest units in inventory which have a cost basis of $10 each, resulting in a cost of sales of $50.

Last-in, Last-out (LIFO)- Under LIFO, the company will calculate the cost of sales utilizing the newest 5 units in inventory which each have a cost basis of $12. This results in a cost of sales of $60 which is $10 higher than that calculated under FIFO. Given that the sales figure is the same under both scenarios, it is not difficult to see that FIFO will result in a higher gross profit than LIFO.

Average Cost- Finally, the Average Cost method calculates the cost of sales per unit as the average of each unit in inventory at the end of the period. In the example above, this results in an average cost basis per unit of $11 ($165 of total cost divided by 15 units). At five units sold, this gives a cost of sales figure of $55. Again, revenue remains the same as under FIFO and LIFO which results in a gross profit that is higher than FIFO but less than LIFO.

We can see that the choice of accounting method results in significantly different gross profits even though the sale price charged and the cash cost spent on the units in inventory remained the same in all three situations. However, to fully understand the impact of inventory accounting methods on profits and margins, we need to explore what happens as prices continue to rise and the company begins to dig deeper into its inventory layers.

Moving the Example Forward

With an understanding of the mechanics of the three methods, we can now move forward to explore what happens in a more dynamic scenario in which prices continue to rise and the company begins carrying inventory from one period to the next. Let’s assume the following sales and inventory purchases for Periods 3 and 4:

Period 3

5 units added to inventory at $13 each

5 units sold for $16 each (period-end cost +$3)

Period 4

5 units added to inventory at $14 each

5 units sold for $17 each (period-end cost +$3)

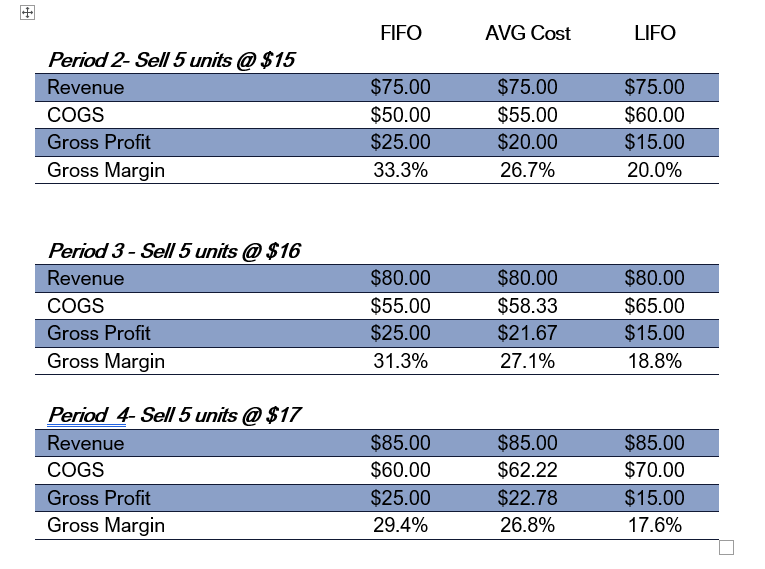

The cost of sales under each inventory accounting method is calculated in each table below:

FIFO

Here we see that under FIFO, the 5 oldest units are expensed in Period 2. They are replaced in Period 3 with 5 more units at a higher cost, but under FIFO, the next five units expensed are taken from the older price layer at $11 each.

LIFO

LIFO is simply FIFO in reverse. In Period 2, the newest 5 units with a cost basis of $12 are expensed. In Period 3, the 5 units acquired during the period with a $13 cost basis are the “last-in” so they are expensed leading to a $65 cost of sales. This repeats in Period 4 as the 5 units acquired during the period at a cost of $14 are expensed.

[An astute reader will notice that by Period 4, the LIFO method has resulted in older, lower-cost layers of inventory building up and that if the company were to begin selling units faster than it replaced them it would soon begin expensing older, lower-cost layers of inventory which would provide an artificial boost to margins. This is known as a “LIFO liquidation” which we will cover in more detail in a later article.]

Average Cost

Average Cost does not follow the same pattern as the previous examples. An average cost per unit is calculated at the end of each period by dividing the number of units in inventory by the total cost of the items. The beginning of the next period carries the remaining inventory over to the next quarter at its average cost basis. Units acquired are added to the beginning inventory and a new average cost is calculated at the end of the next period.

The Impact on Results

The following table shows the sales, cost of sales, gross profit, and gross margin for each method for all four periods.

Remember Period 1 with no inflation. Each inventory accounting method results in the same cost of sales as the cost of units to replace inventory is the same as the original cost of the units being sold.

In periods 2-4, inflation sets in. It costs more to replace the units being sold which leads to a divergence in reported profits for each method.

The Key Takeaways:

The inventory accounting method does not impact revenue. Revenue for each period is the same across FIFO, LIFO, and Average Cost.

If there was no inflation, all three methods would have had 3 months of starting inventory that all cost $10 and the selling price would have been $13. Under all methods without inflation, the results would have been identical with revenue of $65, cost of sales of $50, gross profit of $15, and gross margin of 23.1%

Not surprisingly, FIFO results in the highest gross profit and the highest gross margin throughout all inflationary periods. The FIFO gross margin in Period 2 jumps quickly over pre-inflation Period 1 as the price increases are immediately reflected in revenue but costs still reflect the older, lower-cost inventory. If the rate of inflation stays constant, the gross profit in dollar terms would flatten and the higher sales figure reduces the gross margin percentage. If the rate of inflation accelerated, both gross profit and gross margin would rise again.

Average cost results in the next highest gross profit and margin. It tends to smooth out the highs and lows and results in a more stable gross margin over time.

LIFO gross margin drops significantly in Period 2 as the full impact of the inventory cost increases is immediately reflected in the cost of sales. Not surprisingly, LIFO results in the lowest reported gross profit and gross margin of all three methods during the inflationary periods. This will always be the case except for the “LIFO liquidation” situation discussed above.

The Importance of Inventory Turn

Inventory turnover is a measure of how fast the total amount of inventory is being sold in a given period, typically a year. It can be expressed mathematically as:

The faster a company turns its inventory over, the less the above differences in accounting method will impact results. Even in inflationary times, if a company has a very fast turnover, it may be selling product that was purchased only 2-3 weeks before. The impact of inflation should be lower even with FIFO or Average Cost as it would be unlikely that prices would move materially higher in such a short time. However, the reverse is true. So, to find companies whose results may be artificially benefitting from their choice of inventory accounting method, we should look for companies that utilize either FIFO or Average Cost and that also turn their inventories very slowly. We will examine the case of an extreme example from our research archives- Tiffany& Co.

Tiffany & Co. in 2012- A Clear Example from the Past of Inventory Accounting Inflating Profits

The jeweler Tiffany & Co was one of our favorite inventory stories in the past. A key to understanding the story was seeing that the inventory turnover was only 0.7x per year. At the same time, its key raw materials were rising rapidly in price from 2009-2012:

Gold was $800 per ounce in 2009 and reached $1,800 in 2012

1 carat diamonds rose from $8,900 in 2009 to $9,500 in 2010 to $13,000 in 2011 and dropped back to $12,000 in 2012 according to the Rapaport-RapNet Diamond Trading Network.

Tiffany used the Average Cost method which as we explained above, helps margins in an inflationary environment. Tiffany began boosting prices to reflect the higher cost to replace sold inventory and this was spoken about very favorably in their discussion of earnings:

April 2010 – “sales grew in Americas from higher volume and higher prices per order.”

July 2010 - “Total sales in the Americas increased $25,571,000, or 8%, in the second quarter primarily due to an increase in the average price per unit sold.”

Oct 2010 - “Total sales in the Americas increased $28,252,000, or 9%, in the third quarter primarily due to an increase in the average price per unit sold.”

“In 2010, total sales in the Americas increased $163,726,000, or 12%, primarily due to an increase in the average price per unit sold.”

April 2011 - “Total sales in the Americas increased $59,394,000, or 19%, primarily due to an increase in the average price per unit sold. However, sales in the Americas also benefited from an increase in the number of units sold.”

July 2011 - “In the second quarter, total sales increased $87,790,000, or 25%, primarily due to an increase in the average price per unit sold. Total sales also benefited from an increase in the number of units sold.”

Oct 2011 - “Americas. In the third quarter, total sales increased $55,946,000, or 17%, primarily due to an increase in the average price per unit sold.”

In 2011- “Total sales in the Americas increased $231,212,000, or 15%, primarily due to an increase in the average price per unit sold.”

Remember from the example above, during times of inflation, the Average Cost method will result in costs accumulating in inventory over time. In the case of Tiffany, it took two years for the wave of inflation to really overwhelm the inventory accounts. But investors could see it happening by watching how much inventory was growing in the raw materials segment (about 35% of inventory), into work-in-process (which was only about 5% of inventory), and then into finished goods (about 60% of total inventory).

Note that as inflation picked up, the value of finished goods inventory was actually declining early on in 2010. However, raw materials began to rise rapidly and started to exceed sales growth in late 2010 and all of 2011.

Since finished goods y/y growth was trailing sales growth until the 4Q of fiscal 2011, the company was enjoying robust gross margin growth of 200-300bp as it raised prices and the inflation of commodity costs wasn’t hitting the income statement yet. But, by looking at raw materials on the balance sheet growing 30%-60% y/y in fiscal 2011, one could see that it was only a matter of time before that cost inflation hit results.

By 2012, Tiffany had a different story to tell. It had already taken much of the price increases in 2010 and 2011 due to commodity inflation. With an inventory turn of only 0.7x per year, the higher retail prices had an immediate impact on revenues, while it took seven quarters for the cost of goods sold to start reflecting the inflation. TIF could no longer justify more price increases and may have already priced merchandise above what customers would pay. Suddenly sales growth turned negative with more modest price hikes and negative volume growth and gross margin started to decline by more than 300bp:

April 2012 - “Total sales in the Americas increased $11,022,000, or 3%, due to an increase in the average price per unit sold partly offset by a decrease in the number of units sold.”

July 2012 - “Total sales in the Americas decreased $4,234,000, or 1%, in the second quarter due to a decrease in the number of units sold mostly offset by an increase in the average price per unit sold.”

Oct 2012 - “Total sales in the Americas increased $12,400,000, or 3%, in the third quarter due to an increase in the average price per unit sold partly offset by a decrease in the number of units sold.”

In 2012, total sales in the Americas increased $34,186,000, or 2%, due to an increase in the average price per unit sold partly offset by fewer units sold. In recent years, the Company has increased retail prices to address higher product costs and its strategy is to continue that approach, when appropriate, in the future. The Company did not take retail price increases in 2011 and 2012 sufficient to offset commodity cost pressures the Company has continued to experience. The Company intends to increase prices in 2013.

Another key point to remember about inflation is regardless of the inventory method used – revenues tend to go up. There are many other cost items that may be largely fixed or grow much more slowly such as depreciation, rent, R&D, pension costs. When sales jump on price increases, these types of costs tend to leverage and decline as a percentage of sales. Beware of managements crowing about their amazing new powers to control costs to boost profit margins. There may be higher operating margins, but it is debatable if management had much to do with it. Here is what Tiffany saw during this time:

We already know the price increases boosted sales and the slow flowing of higher-priced inventory into cost of goods sold boosted gross margin. But SG&A as a percentage of sales dropped in fiscal 2010 by 100 basis points, as depreciation leveraged by 30 basis points and lease expense by 70 basis points. In 2011, SG&A was 40 basis points higher but still lower than 2008-09. Depreciation fell further by 80 basis points and lease expense and marketing were flat.

We would argue that depreciation was likely going to be $146 million in fiscal 2011 whether sales were $2 billion or $4 billion. The rent figure would get some benefit if sales were lower as Tiffany paid a minimum fixed figure plus a percentage of rent. However, rent expense was changing due to the company opening more stores but the higher sales figures kept it from being a drag on margins.

We will continue this discussion next week with current examples of companies whose results are benefitting from using FIFO and Average Cost in the current inflationary environment.

Avoid Missing by Subscribing to Peek Behind the Numbers for Free:

Also, please share this with your interested colleagues and friends:

For questions about our institutional research service which provides earnings quality analysis of widely-held names as well as related sell and buy ratings, please e-mail us at behindthenumbers@btnresearch.com.